By Pat Brown

Please don’t take it as hyperbole when I say that The Trip to Italy (2014) is a type of film we should probably have more of. The point isn’t really to heap effusive praise on a film that seems to be getting enough of it, or even to single The Trip to Italy out as a masterpiece. It’s probably not one of those. But it is smart, medium-length, and unpretentious—and very, very funny to boot.

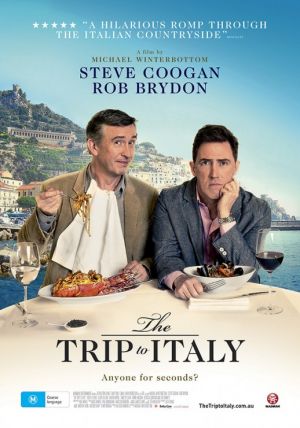

The film is a sequel to 2010’s The Trip and like that film, in the UK it exists as a four-hour, six-part TV series. In the series and the films, the English comedians Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon (actually, they would both be quick to point out, Brydon is Welsh) play slightly fictionalized versions of themselves on a tour of restaurants for a series of articles they’re supposedly writing for The Observer. (Neither man, however, can be observed writing, at least in to Italy.) Over expensive meals, the two bicker and banter, trying to one-up one another with celebrity impressions and only half-jesting digs at each other’s careers.

There are some more extended narrative elements to the series/films. In to Italy, Brydon’s marriage has grown cold, and he finds himself interested in pursuing affairs while he’s away from home. Coogan’s career seems to be more or less stagnant, having become a background player in Hollywood films but not moving beyond that. Both men are coping with minor mid-life crises. But these elements are there mostly to add flavor and perhaps a bit of tension to the real focus, which is the funny---and often even hilarious--chemistry between the two actors.

This time around, the two are following the path of the English Romantic poets Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron, who spend considerable time in Italy in the first quarter of the 19th century. (Shelley even died there, and Coogan and Brydon get a lot of comedy out of mocking the romantic distortions of an 1889 painting by Louis Édouard Fourier of Shelley’s funeral pyre.) The two long-dead Englishmen are points of identification for the comedians, especially Bryden, who see in the (sometimes at-odds) friends Byron and Shelley not just foils for themselves, but probably also symbols of lost youth.

Not that The Trip to Italy is morose. There are moments of dark humor, as early in the film when Brydon insists on reminding Coogan that someday he will be dead, on a slab, being embalmed. The two also visit Pompeii and confront the uncanny sight of the preserved and fossilized bodies of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. But such moments are confronted with what one is tempted to describe as a typically British shrug, or by relaying them into sardonic humor.

The two characters seem well aware that this second trip is a sequel, and seem unconsciously anxious that it be a good one. One of their conversations is about sequels in general, and several deal with sequels more indirectly. In the film’s first near-virtuoso improvised conversation, they discuss (and imitate) the incomprehensible voices in The Dark Knight Rises (2012). The Godfather II (1974) is a constant reference point, as “the only good sequel,” and more indirectly through Brydon’s obsession with impersonating the highly imitable Al Pacino. Toward the end of the film, a re-enactment of a famous scene from Francis Ford Coppola’s best-ever sequel not only serves as a glimpse into the movie-addled mind of Brydon, but also as probably the highlight of the film.

In the US, the six-hour Trip to Italy series has been edited down to a film that runs under two hours. One might think this something of a structural nightmare: how does one make a film out of a television series that is basically a series of conversations? But the episodic structure the film inherits from the show—the series, I presume, devotes one episode each to the different areas in Italy the pair visit—actually gives it a refreshing, relaxed feeling. The characters aren’t rushing toward any goal, they’re not aiming to solve any conflicts, and certainly we will find neither a cliffhanger nor a resolution at the end of the film.

Despite all the references to Romantic poetry and Godard and Fellini films, the film thus comes off as unpretentious because it never feels like it’s trying to sell you on something: a product, a belief, a star, the next film. This isn’t to say that cultural ideology isn’t at play in a film about two wealthy white European men enjoying fine dining on a road trip, or that there are no serious missteps. (One scene, in which Coogan mocks the hearing impaired, is truly grimace-worthy.) It is also, however, a (probably deceptively) simple film that is a great deal of fun to watch.