By Daniel Schimmel

Martin Scorsese has been a topic of debate recently for his harsh opinion of the Marvel Universe. In an interview with Empire, the acclaimed director/filmmaker stated, “I don’t see them. I tried, you know? But that’s not cinema”. He went on to compare those films to theme parks and criticized them of lacking emotional and psychological substance. To an extent, I think we can all agree that his comments were a bit excessive. However, I whole-heartedly agree that there seems to be a trend in cinema of moving away from emotional/psychological stimulation and toward computer-generated spectacle. Films like Marvel’s The Avengers series just don’t carry the same substance as those in Scorsese’s resume. But, with the visionary mind of a creative director and the right filmmaking techniques, I believe they could. James Mangold’s recent Ford v Ferrari (2019) proves he is a director who can take a cliché story and make it new again. Solid performances from the film’s stars are supported by an effective use of sound and cinematography, giving audiences reassurance that a big budget doesn’t always distract Hollywood from making a film with substance.

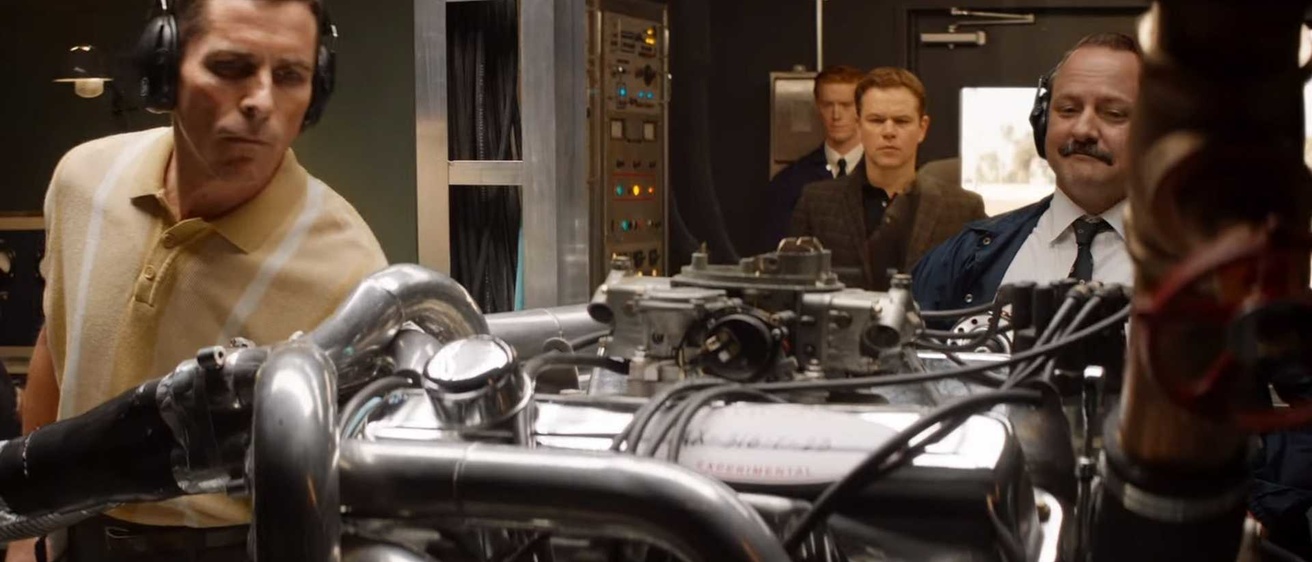

In Ford v Ferrari, Matt Damon and Christian Bale respectively co-star as renowned carmaker Carrol Shelby and daring racecar driver Ken Miles in an underdog story about Ford Motor Company’s battle to create a better racecar than Ferrari. With Ford realizing massive financial decline, innovative marketer Lee Iacocca (Jon Bernthal) suggests the company merge with Ferrari in a deal that would put Ford in charge of production and Ferrari in charge of racing. When Ferrari inevitably refuses, Iacocca pushes Ford into unknown territory by taking a chance at manufacturing and racing their own car with Shelby leading the way. Shelby recruits longtime friend Ken Miles to get behind the wheel, who is qualified for the job and needs it, in order to take care of his family financially. Shelby then battles with Ford executives as Miles’ poor social skills and stubbornness make them reluctant to hand him the wheel. Together, the duo of Shelby and Miles embark on an impossible mission to take down the Ferrari racing dynasty, as well as the equally impossible mission to keep Miles in the driver’s seat.

I was first introduced to the conventional brilliance of director James Mangold with Walk the Line (2005), starring Joaquin Phoenix as ‘the man in black’ Johnny Cash. Tasked with the difficulty of scoring a biopic about one of America’s greatest musicians, Mangold’s sound team successfully re-created the era’s music scene with Phoenix and co-star Reese Witherspoon performing original vocals. Sound plays an enormous role in the moviegoing experience, and the score to Walk the Line helped make the film exceptional. Mangold uses some of the same sound mixing team in Ford v Ferrari (notably Paul Massey, working with David Giammarco and Steven A. Morrow), who takes the film into another level of thrill and excitement. There is an edgy score that reoccurs in the film to introduce racing scenes and add dramatic effect to the whips and turns, combined with authentically recorded sounds that a movie about cars requires: powerful engine roars, shrieking tire screeches, and forceful gear shifts. These noises have never really gained my admiration in cinema because they are often over-exaggerated. Even more, the noises of the final climactic race, including and especially the ‘vrooms’, are often noticeably louder and much more dramatic than previous scenes. Those vrooms of a racecar speeding off is a convention we hear in every racing movie. But a particular scene in this film has made me admire a ‘vroom’ for the first time.

The scene resides at the very start of the climactic race at Les Mans when Miles experiences a simple malfunction in the car: the door won’t shut. He completes his first lap cautiously and pulls over for the Ford/Shelby team to fix the problem. As an audience, this is one of those scenes in an action-packed film where we know the problem is going to be solved but we can’t help but grow anxious as the characters continue to struggle before they figure it out. Here, the problem is solved by whacking the door shut with a hammer; a resolution that is not only fitting but adds both humor and creativity to the problem’s simplicity. Anyway, as soon as the door is locked shut as it was originally supposed to be, Miles gets a thumb’s up from his team and returns one himself before cranking the shift and ‘vrooming’ off. We’ve heard the ‘vroom’ time after time in the film, but here we can’t wait to hear it again. In this scene, Mangold takes the conventions that we’re all too familiar with as movie-goers and adds his own playful thrill supported by his trust in the sound team. His clever use of convention, humor, and anxious excitement echoes throughout the film.

The second Mangold-directed film to surprise me was Logan (2017), a superhero movie darker & grittier than most in the genre. Logan stars Hugh Jackman as Wolverine in a visceral drama that follows the climax of the aging hero while breaking the tired trend of Marvel movies. How does it break the trend? For starters, it’s visually stunning. Throughout the film, Jackman’s Wolverine is subdued in depressingly beautiful landscapes, but balanced with equally effective close-ups in scenes of hand-to-hand combat. Similar techniques can be seen in Ford v Ferrari, where we see Mangold’s creative ability with a camera once again. This go-round, it’s with the help of cinematographer Phedon Papamichael, who previously collaborated with the director on the aforementioned Walk the Line. Shots in the film’s racing sequences are composed for visual clarity and radiance. We get the wide-frame long shots of the cars speeding down the racetrack, but we also get essential close-ups that allow us to sit in the passenger seat next to Bale’s Miles as he masters the necessary turns and shifts. The Atlantic’s David Sims has similar praise writing, “Whenever Mangold and his cinematographer Phedon Papamichael are shooting racing footage, Ford v Ferrari practically vibrates off the screen”. Automobiles and professional racing don’t appeal to me much, but I certainly became a fan for the duration of this film, due in large part to the exceptional camerawork.

If there’s anything we can take out of the year’s best films, it’s the revival of the on-screen bromance. The bond that Damon’s Shelby and Bale’s Miles share is as engaging as that of Leonardo DiCaprio and Brad Pitt’s characters in Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019), which coincidentally takes place in the same decade. I’m not sure which duo I’d rather go out for a drink with, but I’m excited at the idea of either. Damon is a seemingly perfect fit to play Shelby as they share similarities in not only their appearances and mannerisms, but in their personable charm. On the other hand, Bale lost a significant amount of weight (yet again) to play a hot-tempered Miles who is as natured in old-school values as he is competitive. Together, the big-named duo is enticing enough to have starred in their own buddy-cop movie. IndieWire’s Eric Kohn sums up their appeal, saying, “There’s plenty of fun in watching Shelby battle the clock in the face of a daunting engineering challenge, while doing his part to contain the combustible Miles from angering the boss. Bale and Damon look as though they can barely contain the joy of forging an odd-couple chemistry that finds them trading barbs and scheming in equal measures”.

In one of the film’s best scenes, I couldn’t contain my joy in watching their odd-couple chemistry forge on the screen. To save his own job, Shelby had just failed to go the extra mile in keeping Miles on as Ford’s driver for the first race at Les Mans. Ford eventually loses the race and Shelby travels to Miles’ home in an attempt to get him back on the team. After a few verbal jabs from Miles, Shelby tells him, “How long have we known each other, champ? Did I ever break a promise to you? I will put you in the driver’s seat at Les Mans if you just shut your mouth and let me do my thing”. Miles then answers by punching Shelby in the face and the two wrestle each other in Miles’ yard until they exhaust themselves. Meanwhile, Mollie Miles (Caitriona Balfe), is relaxing on a lawn chair as she reads a magazine and allows her husband and his best friend to blow off some hilarious steam and embarrass themselves. I hope we see the actors share more screen time in the future.

A quote at the end of the film resonated with me. Shelby is narrating his best description of what it feels like as a driver during a race. He claims, “There’s a point at 7000 RPMs where everything fades. The machine becomes weightless. It just disappears. All that’s left, a body moving through space and time. 7,000 RPM, that’s where you meet it”. You can look at the moviegoing experience the way in which Shelby looks at racing. Cinema has the power to become immersive. Even big-budget films, including those among Scorsese’s disinterest, as long as they have the necessary tools: a compelling script, worthy performances, a strong aesthetic, and powerful sound. When a director like Mangold utilizes these techniques without swaying far from tradition, everything occurring off the screen disappears. Such was the case for my experience during the racing scenes in Ford v Ferrari, which surprised me as one of the year’s best films.