Tense and subtle, Two Days, One Night is an anxious smolder.

A certain ilk of picture book always made me nervous as a child. In it, a righteously humble protagonist (a donkey, say, or a fly) becomes aware of some crucial truth and must convince his better-off friends to see the world his way before time runs out. Always of some social significance, the truths in these stories are as varied as they are dire—a monster’s on the loose. A best friend has disappeared. The sky is falling.

Armed with only words, our downtrodden hero goes from neighbor to reluctant neighbor, repeating his insights in a pleading refrain; time after time, they reject him. This pattern continues for a harrowing duration until, (in the nicer stories, at least), one accepting soul agrees to lend an ear.

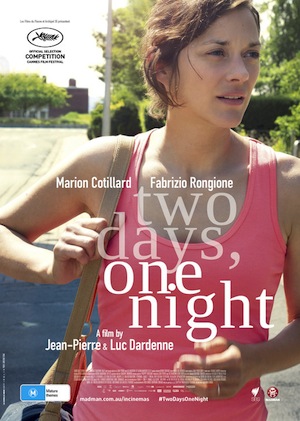

Such protracted moral anxiety lies at the heart of Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne’s latest drama, Two Days, One Night. The story of a woman who overcomes both self-made and socially imposed obstacles to defend her livelihood, the film offers a stark meditation on the limits of altruism. When two parties are suffering equally, ought they fight to preserve themselves, or sacrifice their own well-being to defend one another?

Two Days, One Night begins on a Friday. Roused from a nap on the couch, Sandra (Marion Cotillard) fields a phone call from a coworker, informing her that a majority of their colleagues at their solar panel factory voted to eliminate Sandra’s position, rather than suffer the loss of a 1,000-euro bonus. Fresh from a leave for severe depression, Sandra sinks immediately into a mode of self-defeat—“Je ne suis rien,” she huffs at her husband, Manu (Fabrizio Rongione), wringing a dishcloth in resignation.

But the drive to save her children from poverty energizes Sandra. Encouraged by Manu, she convinces her supervisor to issue a re-vote on the bonus question Monday, when the factory’s menacing foreman, Jean-Marc (Olivier Gourmet), won’t be present to influence opinions. During the intervening weekend, Sandra must convince a majority of her sixteen colleagues to vote to protect her position.

While a simple binary question serves as the central force of tension in Two Days, One Night (will Sandra get to keep her job, or won’t she?), the secondary lines of thought that the plot invites are perhaps the more provocative ones. To what extent does the value of one’s work determine the value of oneself? How do you ask people who are already suffering to suffer more on your behalf? Is that type of question even ethically permissible? And what if your life depends on it?

Ultimately, Sandra’s plea becomes a divisive one. A factory worker knocks his father unconscious after the older man becomes partial to Sandra’s plight. A woman leaves her husband because his reaction to her request confirms his base insensitivity. A new hiree poised to support Sandra fears bullying from colleagues who plan to vote against her. Sandra’s own thoughts about the ethics of her plea take on the form of a whirring gyre: throughout the film, she vacillates between determination and shyness, a need to protect her work (and, by extension, her family and re-budding self-identity) and an underlying empathy for each of her coworkers. Often, it’s too much for her to handle.

By the time the film ends, the relieved suspense of learning Sandra’s fate stands on equal emotional footing with the implied question the movie thrusts at every viewer: “Would I have helped?” This quandary and the ethical implications thereof speak productively to empathy’s power on rational decision-making. “Put yourself in my shoes,” so many colleagues say to Sandra. “I’m not the one who made it like this.” Sandra presents her case in much the same way. But traded empathies don’t solve the problem. Eventually, one situation must be deemed worthier than another.

The sky is falling. Perhaps it’s time for one neighbor to listen.