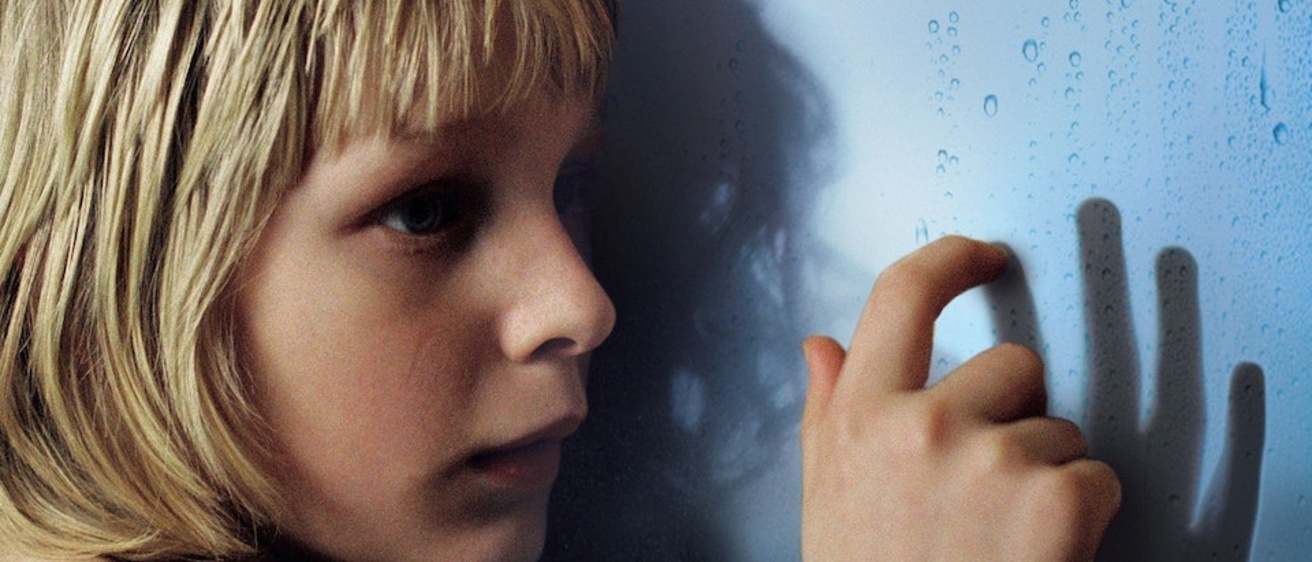

Let the Right One In (2008, dir. Tomas Alfredson), is a horror film in the traditional sense (featuring murderers, vampires, buckets of blood, the whole nine yards). But to me, the real horror lies not in these physical images, but more so in the overwhelming sense of loneliness that this film conveys so well. From the very first shot of snow swirling out of the night, and Oskar staring out his window into that utter darkness, we’re trapped in this barren, desolate place with him. The cold in every shot of this Stockholm suburb seeps into your bones. There is no respite from it–nothing can warm you up here. In fact, the only ray of sunshine seen in the entire film is when Oskar finds the finished Rubik's cube that Eli leaves for him. Oskar has made a connection with someone. He looks up and smiles, squinting against the sun, and suddenly it’s not so cold anymore.

Oskar is a boy aged 12 years, eight months, and nine days. He lives in a less-than-lavish apartment complex in Sweden with his single mother. Eli moves into the room next door, with a man one assumes to be her father, and is at an age that one assumes to be the same as Oskar’s. Both of them are hopelessly alone–one by circumstance, the other by necessity. “Let The Right One In” refers to not only the specific act of inviting in a vampire, but the universally human process of choosing who to let into your world. Your weird little world with all its insecurities and ugliness. As their relationship develops and Oskar finally asks Eli what she is, she replies, “Just like you,” and implores him to “Be me a little.” At first this may seem impossible, as she is everything that he is not. She contrasts him completely with her dark hair, self-assurance, and both the motivation and ability to hurt people, while he in all his pallidness and meekness is barely discernible from the backdrop of dirty snow behind him. Despite this polarity, she suggests that the pair of them aren’t so different after all. Because although he doesn’t tear out people’s throats like she does, he might secretly like to.

Oskar’s violent streak lies dormant, beaten down by the severity of his social situation, until it bursts out of him in a fury in his most private moments. He collects newspaper clippings about local murders and stabs trees with his pocketknife, fantasizing about torturing his bullies the way they torture him at school. Eli persuades him to fight back against his bullies “harder than he dares,” and he does so, at first with trepidation, then with great satisfaction. He stands victorious, grinning down at Conny (whose head he just cracked open with a stick) as Conny screams and writhes around on the ice. This is a horrible thing, and yet we the viewer cannot help but also feel some cold triumph at seeing his torturers get their comeuppance. That is an ugly feeling. Eli and Oskar share their whole selves with one another, and so understand each other on a level that few others possibly could. To have someone wholly know you, and yet love you all the same, is perhaps the most basic and desperate desire of anyone.

Loneliness seeps through the town of Blackeberg, paralyzing every one of its residents. A group of adults spend their hours in the bar, day after day, planning a trip they will never take. Even Oskar’s bullies seem paralyzed by their situation. Kenny, while bashing Oskar with a stick, begins to cry. When Oskar cracks Conny’s head open, Martin and Kenny make no moves to help him, and simply look down at their friend as he screams. Martin, after luring Oskar to the pool to be blinded and drowned, does a little dance with him. These actions suggest that they wouldn’t be hurting Oskar if Conny wasn’t ordering them to do so. But what else is there to do in this place, but plod helplessly down the well-trodden path of your circumstance?

The key to understanding the grim finality of this film is Eli’s caretaker, Hakan. Why is he killing for her? Does he hope she will make him a vampire? Is he jealous that Eli spends time with Oskar, or does he fear for Oskar’s safety? Or is he just a pedophile that has a creepy obsession with a little kid? The last one is probable, given to how prone he is to leering at schoolchildren in gym class, sneaking into locker rooms, and only seeking out young men to murder. But this does not completely account for a loyalty that runs so deep, so unwavering, to the point that he would pour acid on his face and die for her without hesitation. Because of this, the most likely answer that remains is that Hakan is Oskar’s future.

Eli responds to Oskar’s sweet, simple advances in a stoic manner. When Oskar asks her to be his girlfriend, her only reply is “I’m not a girl.” She obviously feels drawn to him, but is not eager to bind herself to him. But all this changes after Hakan’s death. Eli crawls in through Oskar’s window and climbs into his bed, initiates physical contact for the first time, and agrees to “go steady” with him. It is no coincidence that she only accepts Oskar’s offer of attachment after she loses her provider of blood. Viewing the scene through this lens makes her intentions far less romantic, and far more sinister, than they appear to be at first glance. It’s not a stretch to imagine that Hakan started off with Eli in exactly the same way Oskar did, as a young boy in love, and that Oskar is going to meet his same end. Oskar and Eli’s last little morse code messages to each other (“kiss” and “little kiss”) are poisoned with the disturbing realization that this pure and innocent love is doomed to curdle into something evil. Oskar will spend his life murdering for Eli, the same way Hakan did, until he dies for her. But they won’t be alone anymore, at least for a little while. “It’ll be you and me.”