By Mallory Hellman

Like its protagonists, Dear White People is brilliant, funny, and righteously pissed off.

Quick. Think about the last mainstream American film you’ve seen whose central protagonist* is black.

Got it? Good. Now, some further questions: is that character a professional athlete? A musician? A revered but tragically martyred civil rights activist? Does your character struggle with addiction? Poverty? An abusive or neglectful family structure? Does your character carry a gun? Has s/he ever been forced to resort to sex work or drug trafficking to survive? And, if your film has a happy ending, did your character finally overcome his or her circumstances with help from a well-meaning white mentor?

I see you nodding. Or maybe looking askance.

Perhaps it’s more productive to consider the inverse. Have you ever seen a film with a black protagonist whose material comfort stems from a white-collar job? Who attends or attended an Ivy League school? Who studies economics or biology? Who lives in a suburb? Is a writer? Is gay?

Justin Simien’s Dear White People both elegantly and provocatively explodes common media stereotypes of black youth. At Winchester University, the fictional locus of the film’s goings-on, privilege is part of the donné. Campus dining rooms come adorned with gilded crests and chandeliers, student publications double as hiring pipelines for The New York Times, and—as is the case with so many historically white institutions—students of color are relegated to a single residence hall.

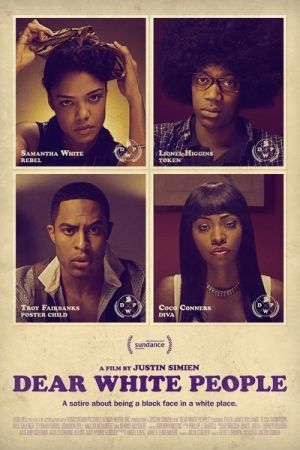

That hall becomes a fulcrum of controversy when Samantha White (Tessa Thompson), a film major known for her radical politics and incendiary talk-radio show (from which Dear White People derives its name) beats incumbent Troy Fairbanks (Brandon P. Bell) in an election for house representative. Fairbanks, the well-heeled son of Winchester’s dean of students, supported an initiative to randomize housing at the university, a move that White believes will dilute the proud countercultural history of their house.

The tension between Fairbanks and White—and their respective, brilliantly portrayed posses—contributes thoughtfully to the film’s broader discussion of the role of privileged black students in the historically white institutions that have ostensibly accepted them. For Samantha White, the struggle is one of clinging to blackness: of remembering and honoring her racial history while mobilizing vigilantly against the school’s subtle (and not-so-subtle) contemporary prejudices. She inhabits the unlucky position of fighting on the front lines of a war whose central antagonists—both white and black—are convinced that the conflict is over. Insisting that Winchester is beyond racial issues, the school’s president, in one climactic scene, accuses White of wanting to be victimized.

Troy Fairbanks, on the other hand, has long been inculcated to craft his ambitions according to traditionally white metrics: a high-caliber education, law school, a political career. Fueled by his father’s rivalry with Winchester’s white president, Troy works doggedly to stay on top, even going so far as to date the president’s daughter (actualizing the white father’s implied fear of black sexuality). Also in deference to this competition, Troy reluctantly turns himself against the president’s son, fellow classmate Kurt Fletcher.

Indeed, the complicated relationship between Troy and Kurt illustrates poignantly the contrast between old privilege and new, between the uneasy place of minorities in powerful institutions and the recklessness enabled by the majority’s security there. Put anecdotally: Troy runs for student government positions. Kurt edits the campus humor magazine. Troy curates his public appearance meticulously, incurring the wrath of his father for any perceived misstep. Kurt is crude and hateful with impunity, wielding his family name at the slightest hint of a confrontation. And when Troy tries to sit at Kurt’s table (both literally and figuratively—he joins a poker game designed to cull out new recruits for the humor magazine), he’s soundly rejected.

Dear White People culminates in the surprising “Release Your Inner Negro” party, where both slurs and punches are thrown, an unlikely hero makes his debut, and a whole new set of questions is put to the local powers that be. Like any socially conscious project, the film doesn’t purport to answer these questions, but instead leaves its audience full—full of astonishment, of bemusement, and even of a bit of rage. It’s a potent emotional cocktail for such an entertaining movie and one, I daresay, we could all use a dose of.

*And I mean protagonist. The winningly self-effacing best friend of a leading rom-com lady doesn’t count, nor does the “sassily” jocund sales clerk whose one-liners serve as her only character development.