By Duncan Sinclair

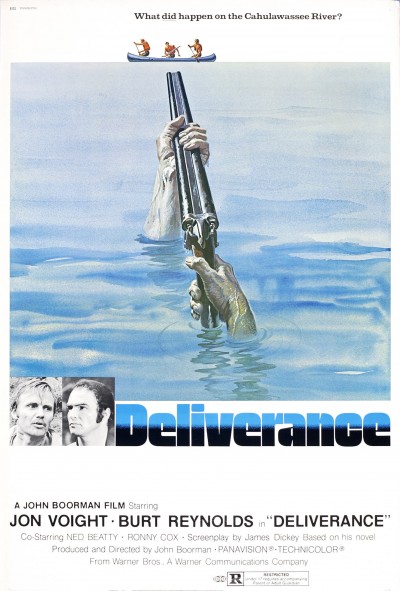

Deliverance, John Boorman’s 1972 survival film, is a tense, disturbing tale of survival. Four businessmen travel down South for some recreation, but end up trapped in the woods beset with injuries and paranoia. In order to make it out of the wild they must utilize their primal will to survive and make decisions they never thought they would face. The film is sharply edited, never allowing the viewer to feel safe. Be it a gun, a cliff edge, or a raging rapid there is always danger lurking in the frame. And indeed, an even greater danger lurking out of frame.

The film begins with the four men arriving in the fictitious Cahulawassee River valley for a canoe trip. Their intent is to make good use of the land before the valley is flooded to build a dam. Despite the four men’s general likeability it is hard not to view their vacation as a form of slumming. “Roughing it” in the wilderness before retreating to their lives of convenience.

Three of the men are aware of their displacement, occasionally condescending towards the locals but ultimately conscious of their class differences and treat the locals with respect, while Burt Reynold’s Lewis, the group’s de facto leader, comes armed and ready to prove he is as rugged as any country-folk. His “because it’s there “response when pressed on his motivations for coming reeks of entitlement rather than George Mallory’s sense of adventure. The survivalist speech he gives in the face of danger sounds awfully rehearsed, but once given the chance to walk the walk he fails pitifully.

It seems at times that Deliverance’s legacy is that creating/perpetuating the stereotype of “hillbillies” as violent, inbred hicks. But for that to be the sole takeaway from this film one must watch it solely as a survival-adventure, investing oneself solely in the protagonist’s plight. Boorman holds on wide shots for many segments to isolate the characters and heighten their sense of danger, but as the film states early on, the setting itself is in danger. Once the canoe trip is over, the valley will be flooded and the trees, cliffs, and any local structures unable to leave will be destroyed.

The men justify the actions they took to make it out of the valley alive. But the doubt and guilt felt by Jon Voight’s Ed seeps of the screen. What sins of the bourgeois have been buried in the rural landscapes, hopefully out of sight forever? The film’s haunting final shot represents the unconscious fears of all affluent Americans: that some day they will all “have to play the game”. A game that they ultimately started.