By Lee Sailor

Lee Sailor: In your class, you mentioned early filmmakers, German expressionists, I think, who were interested in occultism and the occult. I was wondering if you could elaborate on that. Like, were they worshiping the devil or something?

Andrew Owens: No, no, at least not that I'm aware of. Yeah, my generic bag is horror, which is really where I settled into my research. But specifically, occultism has become very interesting to me.

The cinema has a long history of being interested in things like the supernatural, the occult. Particularly, I think, because it’s been a realm of the unseeable, of things that you couldn't see [or that] you're not supposed to have access to. Early on in cinema, that was the same thing. Cinematic technologies were supposed to give audiences views [of] things they had never seen before. So there’s a way in which the cinema has acted as a metaphor for the supernatural. It was quite magical to many people, at least early on.

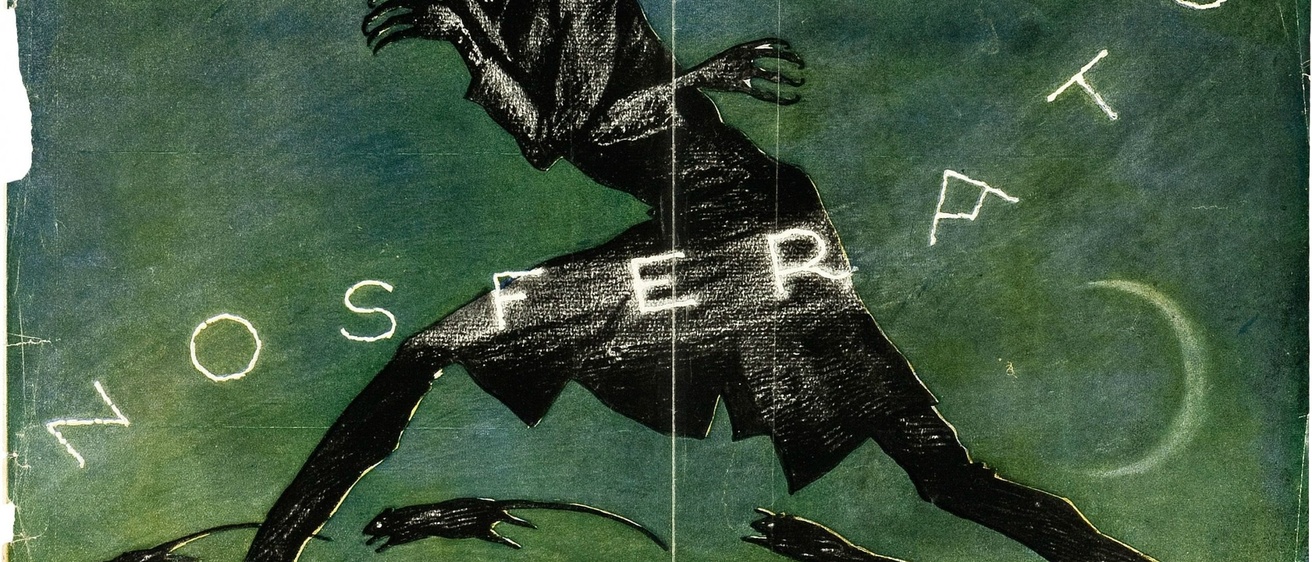

With German expressionism, [for example] the gentleman who was the art director for [Nosferatu], Albin Grau, was an avowed occultist.

LS: Was there an increased interest in occultism after WWI? Do you think that the war and its horrors may have played into the appeal of these beliefs?

AO: Yeah, potentially. There's a lot of conspiracy theories surrounding both of the World Wars in [asking], you know, what started it? What ended it? Were there supernatural powers involved, somehow, that either brought it to a culmination, a beginning or an end? But particularly [you find this] after the Second World War. People were quite literally disillusioned with the world. In the aftermath of the First World War, no one had really seen anything like this. The reaction seemed to be, how in the world could this happen? And how do we stop it from happening again?

Well, then when the Second World War comes around…then people are really like, how did we let this happen again? People were quite literally disenchanted with the state of the world. A lot of people, mostly continental folks in Europe, wrote about the fact that [they had been] pushed all of this stuff, you know, modern, modern, modern, modern warfare, modern technologies.

They saw that as [detrimental], with human beings losing their connection to nature and things that are otherworldly. [Things] that had been cast aside in favor of modernism. So I think what we see there is a backlash against modernism and an interest in returning to pre-modern times, not prehistoric times, but at least times that were a little simpler.

LS: I know this is something you have a book about, but if you could give a brief overview of how this has played out in recent years—how the occult functions in current cinema and television and a history of that evolution?

AO: My book research begins in the year 1960. The 60s are remembered as a decade full of sex, drugs and rock and roll, right? But part of that is also adjacent to a hugely revived interest in the supernatural and the occult. You can [see that in] things like Ouija boards, yoga, and drug cultures—LSD, marijuana, pick your favorite.

All of these alternative spiritual beliefs coalesce in the American entertainment industry and many in Europe, particularly in the U.K., selling the occult as a brand of entertainment.

In the 60s, it turned out that what occultism actually was wasn’t very interesting as far as the American entertainment industry was concerned, in terms of not selling. [So instead], they were selling you devil worshipers. Things like Rosemary's Baby that comes out in 1968 and does phenomenally well. It's one of the top ten grossing films in 1968. But if you read about occultists at the time, they’re saying, “No, we don't do any of that.” Most of what we recognize contemporarily as magik or witchcraft are nature-based religions. They're pagan. Things like wicca…have nothing to do with the devil or Satan, because that’s a Christian concept.

This is where if you chart the history of the modern horror film…you can put your finger on the pulse of what culture is thinking about.

In the late 70s and early 80s, for instance, there was the slasher film. So a lot of people argue that the slasher film is a direct result of the rise of second wave feminism, of gay liberation, of [that] sort of topsy turvy rethinking of American morality and values when it came to gender and sexuality.

In the 80s, the horror film really morphs in quite interesting ways, I argue, because of the arrival of the AIDS epidemic. It's an eerie mirror sort of to what we're experiencing right now. About infection and contagion and who's safe, who's not.

As we head into the nineties and the new millennium, television is just lousy with occultism. Now, there is just so much occult TV in the world. One of the things that I looked at is what began in the 90s as the WB, the offshoot television network of Warner Brothers, which then morphed into UPN, and now is the CW. The CW, at this point, more or less is keeping the lights on through occultism in their biggest shows. Things like The Vampire Diaries, The Originals, Nancy Drew. That network is building its brand on the back of occult narratives, which I find really fascinating.

That's not to say that movies aren't doing that. But because we've had a shift now where most major players in cinema are doing superhero movies, some of the most interesting occult horror, specifically, is being done in the indie market, in the indie circuit. A24 is doing a lot of that.

Television is interesting because it’s guarded by a completely different set of rules than movies. Network television has always been beholden to the content and restriction standards of the FCC. In the 60s, there’s this huge ballooning up of horror and occult shows, but it's mostly very safe in terms of being done through the format of the situation comedy. Things like Bewitched, The Addams Family, The Munsters, and I Dream of Jeannie. That's not to say there weren't some that were more serious before that, particularly in the late 50s and early 60s, you have things like the Twilight Zone. And there was a kind of competitor of the Twilight Zone on NBC that was hosted by Boris Karloff called Thriller.

LS: One film Bijou is hoping to play for a virtual screening is Haxan, a silent film from Sweden and Denmark about witches and witchcraft. It's an interesting example because it had two releases. First in 1922 and then again in the 60s, with a [shortened] version narrated by William S. Burroughs. How do you think those releases fit into their cultural context, both the original release and the later one?

AO: Certainly in the 20s, it would be analogous to what we talked about earlier with the end of the First World War. And thinking about what caused this. Did witches cause the First World War? Or did they stop the First World War? In the 60s, it was very much a product of the fact that occultism was in. That far out grooviness of occultism and alternative spirituality mixed with the sort of rock and roll drug culture of the 60s, really was rife for being exploited by the American entertainment industry. A lot of films from Europe specifically began to flood American cinemas in the postwar period because of the climate of Hollywood.

We get the arrival of true arthouse theaters in the postwar period. A film like Haxan probably did well in the 60s because it was a European import, which a lot of people were into as…a cachet of a certain kind. It also potentially gave folks in the 60s who were dabbling in occultism or witchcraft the opportunity to look at the history of witchcraft and say, “Oh, this has been around for quite some time. What I'm doing is not necessarily new, but it has a long and storied history.” Now, Haxan is not a documentary, it's a fiction film.

LS: Sort of like a proto-exploitation film.

AO: Right. And one of the arguments it's making is basically linking witchcraft with female hysteria. Which, eh...

But again, it really is interesting culturally because of the rise of second wave feminism in the 60s. There are a bunch of films in the 60s and 70s where you have housewives who were staying home all day and are at the end of the rope, [so] they get into witchcraft for some kicks. That’s a theme that repeats over and over again. So that's a really interesting moment to look and see how the rise of witchcraft and magik deals with changes in American gender and sexuality.

LS: Given the background you mentioned of unrest after two world wars and the AIDS epidemic, given the current era with large scale protests and the COVID pandemic, do you think it's likely, that this might play into another resurgence [of occultism]? Or do you think that because there's already far more occultism in media now, it might play out differently than in the past?

AO: [It’ll be] interesting to see. The occult is really a sort of grab bag term for a set of religious or spiritual beliefs or belief systems in the world. And I think why things like spirituality or belief systems seem to be particularly an issue in times like we're going through is because we as human beings want explanations. We want to know, Why is this happening? Why is this happening and what can we do about it?

It’ll be fascinating to see, once we get on the other side of this pandemic, do things like contagion and infection become new fodder for the American entertainment industry in film and television? And is there something occultish about that? I don't know. But I think that there will be certainly a revived interest in entertainment that deals with belief systems and about how we as human beings reconcile when things happen to us that are completely beyond our control.

Dr. Andrew Owens is a professor of Cinematic Arts at the University of Iowa and the author of Desire after Dark: Contemporary Queer Cultures and Occultly Marvelous Media, which will be published by Indiana University Press in March of 2021.