By Michael Davis

I had just turned 11 when I saw Pleasantville for the first time in 1998. At that young of an age, I was not yet enamored with understanding the deeper socially relevant aspects of a movie. When I got out of the theater, I could tell my father what I liked about the movie in general terms. “The acting was great,” or “It was very funny.” It was not until I saw Pleasantville, however, that I began to get a deeper understanding of the themes of the film, or any film for that matter.

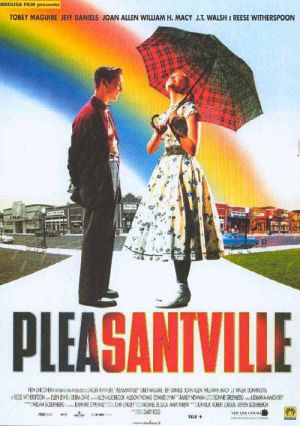

Pleasantville starts off simple enough, as siblings David (Tobey Maguire) and Jennifer (Reese Witherspoon) are trapped in your average high school existence, totally fine avoiding each other for fear of letting someone know they are related. David is an avid fan of a black-and-white 1950s sitcom called Pleasantville. A marathon of the show is scheduled for a Friday night, which unfortunately coincides with Jennifer’s need to use the television. A fight over the remote ensues, and they are both magically - thanks to the intervention of a TV repairman played by Don Knotts - transported to the Pleasantville depicted in the sitcom. Once there, they meet their Cleaver-esque parents, played William H. Macy and Joan Allen.

It is no surprise that Maguire’s character finds his new world both fascinating and homey, given his fandom of the show. Witherspoon’s Jennifer is having no such luck with her surroundings. They are foreign to her, leaving behind the fashion, style, and freedom she had so enjoyed in the 1990s.

The world of Pleasantville evokes a strong nostalgia for Main Street USA – a brand of wholesomeness that would become intolerable for a cynic. Everyone knows your name, no one is left out, and the basketball team never loses. Ever.

And don’t even think about sex. It doesn’t exist, at least not in any form that is discussed. As was customary during the ‘50s, men and women slept in separate beds.

While Maguire’s character enjoys the experience as a reflection of his own personality, Witherspoon rejects it by her own brand of rebellion: sexuality. The passion and liberation that she injects into her new world is changing it forever. The black-and-white tones turn into vivid color schemes when these teens uncover what their bodies can do. In addition, listening to “inappropriate” music or reading “controversial” books has the same effect, causing the uninitiated to perk up in interest. As a result, the town’s mayor, Big Bob (J.T. Walsh), fights back, outlawing all forms of self-expression that result in the color change, turning those already changed into social outcasts.

Writer and director Gary Ross uses the fear and paranoia of the 1950s to great dramatic effect in the film. For those living during this decade, it was a jumble of emotions. The tremors of World War II could still be felt; a nation of prideful Americans are fearful of the next great threat. The civil rights of African Americans is slowly seeping into the consciousness of a culture that had long ignored the scourge of racial discrimination. The sexual liberation of men and women would arrive soon after.

Ross addresses these topics in an easy-to-digest manner, using the era as microscope of thought and action. The men and women of Pleasantville see these changes as an encroachment into their perfectly constructed worlds where if we don’t speak of certain things, they don’t exist. If everyone is depicted in drab colors, then everyone is the same. If everyone is the same, we don’t have to worry about our differences.

The hate and discrimination that the men and women encounter for being “colorful” is an honest reflection of the engrained racism at the time, which has never really been examined, or even

solved, since Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and the Civil War. Some might suggest that this theme lacks in subtlety, but Ross is right to hammer it into our minds, both as reflection of past and current prejudices. Racism in the 1950s was not subtle, and for many Americans living in 2015, it still isn’t.

With the still burning freedom from World War II, 1950s America was ready to experiment, and sex was the logical choice to combat the perceived righteousness of wholesomeness and abstinence. With sexual exploration, comes the empowerment of women and different sexual desires. The 1950s was not too far removed from the “Gay Panic” defense that was made infamous in the 1920s to acquit murderers, fearing even the touch of gay men and women. From the reaction of the townsfolk to these free-thinking men and women in Pleasantville, their worst bigoted fears have come to fruition.

As has been the case throughout history, freedom of expression wins out in Pleasantville through hard-fought battles against the tyranny of censorship and discrimination. The message of acceptance shines even brighter than it did in 1998 when this movie was first released. For some, the battle against oppression continues, a hollow reminder that we haven’t surpassed some of the outdated norms of the 1950s. As a form of entertainment, Pleasantville succeeds on its own terms. But as a social critique of our shared past and current history, it has very few equals in the last 20 years.