By Emily Brown

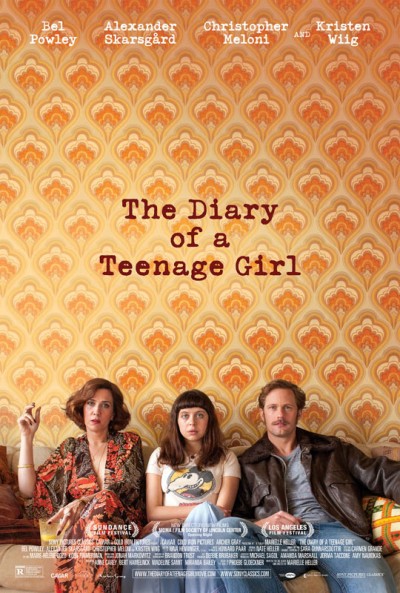

In The Diary of a Teenage Girl, the first thing you hear is a voiceover of fifteen-year old Minnie Goetz. Minnie, played by Bel Powley, has an open, sweet face with incredibly expressive eyes. This is fitting, given that the film centers on how Minnie sees the world—her experiences, delights, anxieties, fears, disappointments and triumphs are what move us through the plot. The film, an adaptation of Phoebe Gloeckner’s “novel with graphics” of the same name, is directed by Marielle Heller and follows Minnie, who lives with her mother (played by the dynamic Kristen Wiig of Bridesmaids and SNL fame) and younger sister in 1970s San Francisco. (Minor spoilers below.)

What Minnie wants, more than anything, is to be loved. Her mother won’t touch her anymore (due to a Freud-loving ex-husband who said that Minnie’s need for maternal affection was sexual) unless she’s wasted. For Minnie, love and sex seem fundamentally intertwined. But the film takes Minnie’s desire and agency seriously.

When Minnie begins an affair with her mother’s boyfriend Monroe, we see it through Minnie’s perspective. The scenes between her and Monroe (True Blood and Generation Kill’s Alexander Skarsgård) are shot as intimate, sexy moments. In another director’s hands, these scenes might have become more pornified or moralizing, but Heller isn’t afraid to show the sexual energy between these two characters or the emotional and frankly terrifying aftermath of their relationship. Monroe, who we first really see shot from below with a hazy glow that transforms into bursts of flowers surrounding his face, is both a dream-boat and a creep, an alcoholic skeez and a nice guy, and it’s easy to see why both Minnie and her mother are drawn to him. The film never lets the viewer off the hook when it comes to confronting the disquieting reality of Minnie and Monroe’s affair. When, in bed after an afternoon romp, Minnie lays her head on his shoulder and asks, “What’s your favorite color?” you could hear an audible gasp from the audience. This is the pillow talk that this film provides—one that never lets you forget how young she is.

The film is beautifully shot and feels like a dream of San Francisco—fun, colorful, multicultural, never boring but rarely scary. It’s a hazy city, seen through Minnie’s eyes. In her drawings, she’s gargantuan, towering over the buildings, her features grossly exaggerated. And that’s probably the most powerful thing about this film—how centered Minnie’s bodily experience of her life is. When she worries that she’s too fat to be loved, as an audience we both empathize with those adolescent anxieties and want to reassure her that’s she’s beautiful. Eventually, what Minnie realizes is that the love has got to come from her, from her mind, from her art, from her soul. More than anything, this film is about what it means to grow up, to grow into yourself. It’s a beautiful thing to watch.