By Mallory Hellman

When I was nine, I kept a Saturday ritual: after breakfast, I’d slick my hair into a messy pompadour with water from the bathroom sink, clamber onto the roof of my clapboard tree fort, and loop the Empire Records soundtrack on my DiscMan until someone noticed me.

I’d persist like that for hours, attempting to strike a position of careless repose as I gazed listlessly at the branches of our family’s magnolia tree. I felt like a total badass. I still hadn’t seen the film.

But perhaps the feeling its music gave me was just the point. Empire Records, for a film that was both a critical failure and a horrible box office flop, has held tremendous cultural staying power—and not for the purely campy allure its cult cousins like Rocky Horror and Love Story have accrued. Empire Records speaks to the distraught, earnest seventeen-year-old inside each of us, the one that goads us to shake up the status quo from time to time—the one whispering, “Damn the man. Save the Empire.”

The story of an independent record store on one eventful day that might be its last, Empire Records seizes on the 90s zeitgeist of empowerment through teamwork, following a friendly band of adolescent burnouts as they attempt, in their humble and sexy ways, to rescue the place they love. Guided by a fatherly manager (Anthony LaPaglia), the group breaks the law, sleeps with has-been pop stars, stages a funeral for someone who’s still living, and culminates the day’s work with a gargantuan dance party.

While it sounds like (and, in some ways, is) typical pre-9/11 stoner fare, Empire Records transcends the genre by allowing its viewers to become attached to characters who serve both as hysterical representations of American adolescence in the 90s and as an empowering commentary on the countercultural power of youth.

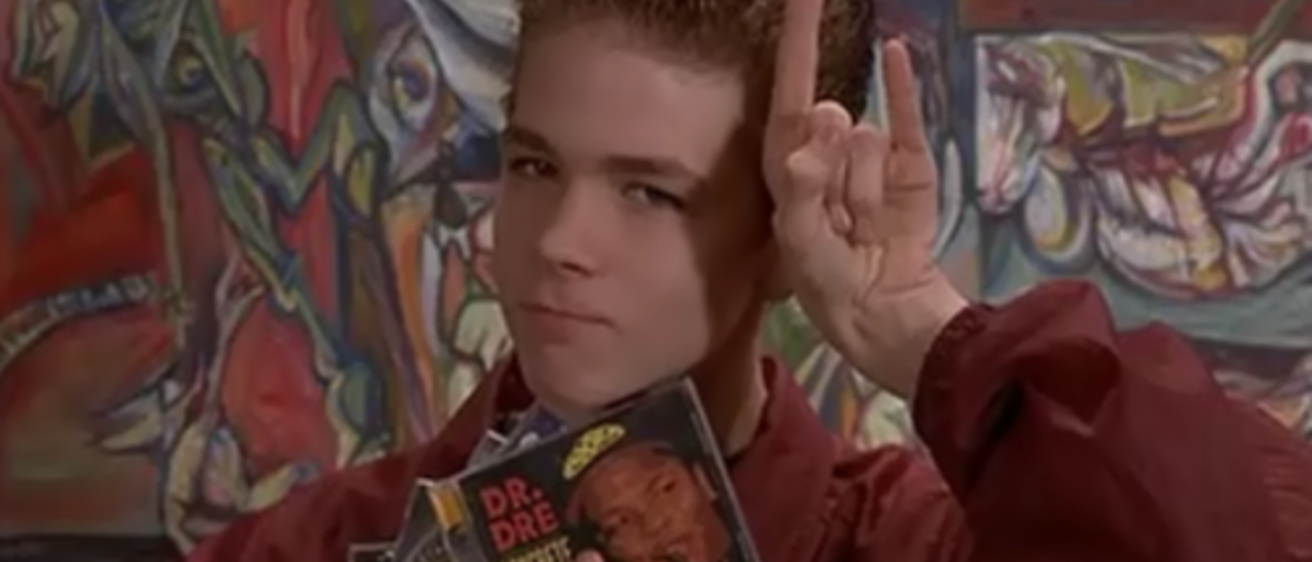

To fans of the niche teen comedy, Empire Records’ cast list is gratifyingly familiar: the Harvard-bound, sexually repressed schoolgirl who lives in a secret world of anguish (Liv Tyler); the unwittingly dreamy artist who loves her (Johnny Whitworth); the tortured soul who puts up a mean front (Robin Tunney); the slut (Renée Zellweger); the stoner (Ethan Embry); and the brooding sage who sets the story’s plot in motion (Rory Cochrane).

Empire Records begins at midnight, when Lucas, a ne’er-do-well weirdo in a turtleneck and black leather jacket, is charged with closing the shop. After stumbling upon his manager’s plans to sell Empire to a larger franchise, Lucas snatches the company savings, drives them to Atlantic City, and loses them all over the course of an hour.

During the hectic day that ensues, Lucas’s manager, Joe, attempts to forestall the store’s bankruptcy while the other employees sort through a windfall of personal dramas in their attempt to make Empire a welcoming place for fizzling pop idol Rex Manning (Maxwell Caulfield). When the forces of everyone’s ambitions collide, a delightfully offbeat chaos results.

When Empire Records was released nearly twenty years ago, critics whined that it was disjointed, lightweight, that it was a “soundtrack looking for a film.” Roger Ebert went so far as to say that the best thing about the movie was its actors’ potential for future achievement.

But so much of what led Ebert to dub the film “a lost cause” is precisely what makes it great: like the generation of slackers and “pretty, gum-chewing freaks” it represents, Empire Records never takes itself too seriously. While a singular point of tension (will the store close?) is established early on in the story, the film doesn’t feel the need to harp on the problem or even put too much pressure behind it. While we’re waiting to see whether the issue of the missing cash will be resolved, we’ve got a floor show of loveable misfits to entertain us. None of them seem to care what will happen tomorrow, and for the pleasant span of a couple of hours, neither do we.

Empire Records is a comedy in the truest sense of the word, with numerous fantastic storylines vying for the spotlight, characters whose screw-ups make them all the more endearing, a resolution that’s satisfying without being sappy, and, yes, one hell of a soundtrack.