By Mallory Hellman

Nothing makes a man so vain as being told he’s a sinner.

Americans are stupendous at nostalgia. We express it daily with our pants. Our facial hair. The tortured rebirth of the retro Doritos bag. For a country so relatively young, we bear an almost compulsive need to reflect, and nowhere is this longing so acute as in our cinema. Particularly in the last two decades, some of the most celebrated films in the U.S. have engaged with our fraught cultural history, casting a tear-glinted eye back to recent eras to examine how righteous we were. How misguided. How hot.

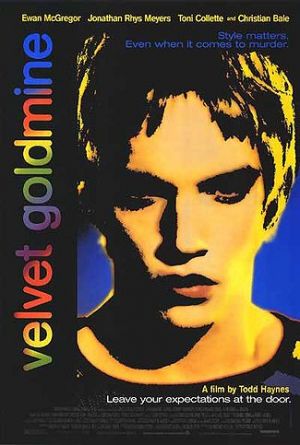

One of the most cult-iconic nuggets of the country’s late-90s pining for all things glam, Velvet Goldmine tells the story of a pop god and his demise. Part cultural study, part fairy tale, and part campy homoerotic romp, the movie does something I’m convinced only cinema of its era successfully can: it blurs the line between narrative film and feature-length music video, casting a glitter-spackled middle finger at anyone who asks it to choose.

The setting is London. The pants are audaciously tight. Velvet Goldmine begins as thickly Bowie-esque rock singer Brian Slade (Jonathan Rhys Meyers) gets assassinated before a crowd of thousands in a sold-out concert hall. Ten years later, long after the murder has been exposed as a hoax and Slade has disappeared from the public imagination, journalist Arthur Stuart (Christian Bale) attempts to find out what actually happened to the fallen pop icon. In his quest, he interviews Slade’s first manager (Michael Feast), his ex-wife (Toni Collette), and Curt Wild (Ewan McGregor), the American rock star who loved and inspired him. Scattered throughout are tidbits of Stuart’s own history, which entwines more intimately with Slade’s than the film’s setup would seem to portend.

What saves Velvet Goldmine from becoming a total knock-off of VH1’s Behind the Music is the film’s scrupulous self-consciousness. Every time it teeters on the brink of sentimentality, an outrageous musical interlude or dash of poetic collage reminds us that the whole thing, like Slade’s life itself, is an act. This relentless examination of performativity transforms the film from a well-executed nostalgic wink into a serious piece of culture in its own right.

The characters in Velvet Goldmine demonstrate elegantly both the ease with which a social posture can be assumed and the difficulty of sustaining it across the span of a public career. Brian Slade speaks in over-the-top sexy aphorisms and pouts his way through situations beyond his psychological capacity to handle. Mandy, his ex, fluctuates almost maddeningly between her natural American accent and a hyperbolically posh British one. But perhaps the most interesting study in pop’s implicit contrasts is Curt Wild: with greasy shoulder-length hair, a twiggy body, and the vocal affect of a GI Joe, Wild seems an oafish puppy thrust into the shell of a rock star.

The care with which Velvet Goldmine presents these characters mimics the care with which they’d curate their own appearance, creating a film that’s quite a spectacle, while commenting on the nature of spectacle itself.

Indeed, perhaps what remains most impressive to me about Velvet Goldmine is the shape of the thing: the film’s ability to conjure up so many non-Bowie Bowie songs, to create dreamy interludes that spin between satire and profundity, and, in the end, to tie the its narrative together with the completed journey of a single object. Whether you’re looking for a musically enhanced stroll down memory lane or an incisive commentary on the manufacture of pop culture, Velvet Goldmine is one hell of a trip.