By Nathan Kouri

A neurotic couple chases crabs around an apartment to try and re-catch their dinner in a brutally honest reinvention of the romantic comedy. Quick, what movie is it? No, not Annie Hall, but Tsai Ming-liang's experimental softcore rom-com musical horror satire The Wayward Cloud (2005).

Why the bizarre mashup of genres and forms? Tsai is one of the world's most revered filmmakers—the Louvre even invited him to make his film Face (2009) in the museum, afterwards adding it to their collection—and he's clearly not just goofing off. So what is he up to?

The Wayward Cloud goes to great lengths to reveal the many layers of its central relationship: together and apart, real and imagined, sweet and violent, sexual and impotent. While the film's use of long shots and sparse dialogue might seem superficially distanced from its characters, it expresses their inner lives through less conventional means by exteriorizing their fantasies, connecting them to the audiences’ own imagination, and linking these personal fantasies to collective ones.

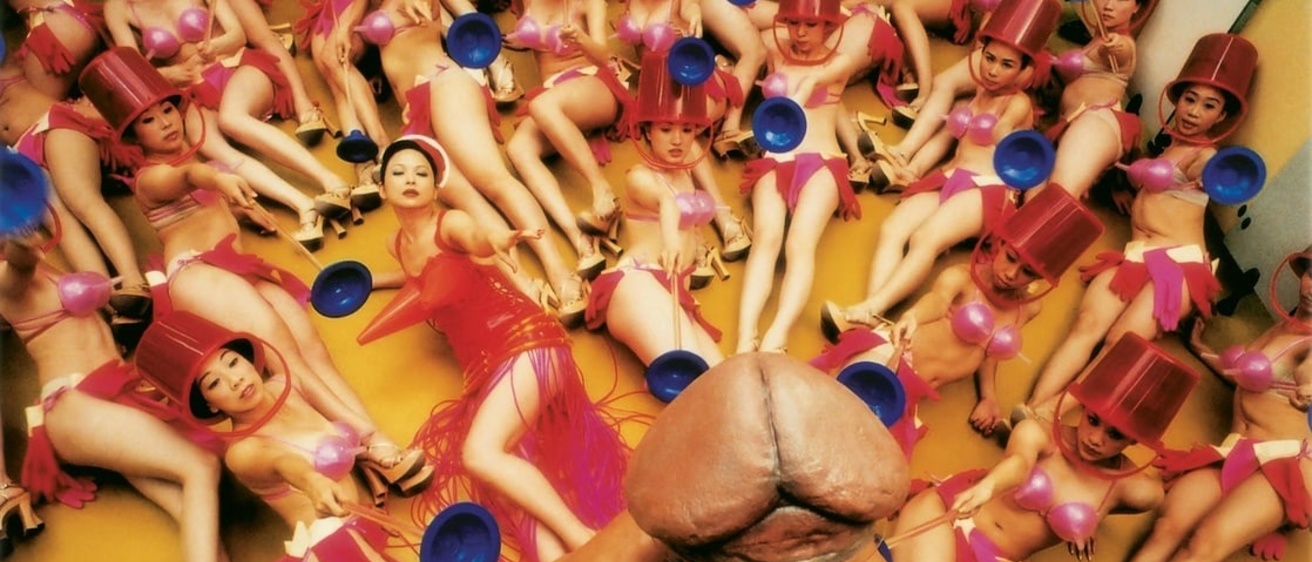

In this way, the collision of the seemingly incompatible elements of musical numbers and explicit sex scenes makes sense: both are by nature intense representations of fantasies. As put in Adrian Martin, Helen Bandis, and Grant McDonald's piece on the film in Rouge 11, "The Wayward Cloud brilliantly demonstrates the startling analogy that Paul Willemen once suggested between sex scenes in porno flicks and the song-and-dance numbers in musicals: both offer...the spectacle of a fantasised abundance in place of a real, material scarcity.”

And what is more driven by, and clouded by, fantasy than love and sex? The musical numbers in the film, campy yet sensitive, express feelings left unsaid or only implied in its main action, nearly without dialogue—loneliness, political dissatisfaction, sado-masocistic desire—and the last two both express anxiety about fulfilling societal expectations of gender roles. Hsiao-kang can wear a merman costume with elaborate makeup in a musical fantasy, and a dress in another, but not in his "real," daily life. This exteriorizing of interior queer fantasies returns in Tsai’s 2015 short no no sleep, when two men sit next to each other in a bathhouse and the ripples in the water make it look like there’s a sexual interaction between them, but under the water there’s not; a brilliant separation of an action and its representation. Tsai's films often queer things in representation that are straight in their diegetic reality. For instance, his mise-en-scene repeatedly emphasizes the features of Lee Kang-sheng’s body, even (and most unconventionally) during heterosexual sex scenes in The Wayward Cloud and What Time Is It There? (2001). Tsai’s films create images as physical manifestations of intangible dispositions for both his characters and, unavoidably, the filmmaker and film audience.

The Wayward Cloud uses genre to shape and interrogate a different set of fantasies, playing with the audience’s expectations insightfully and cruelly. It's full of conventions from romantic comedies like, as mentioned above, recreating Annie Hall’s famous lobster scene with crabs, but they’re subverted when applied to the dysfunctional relationship of the main characters, Hsiao-kang (Lee Kang-sheng) and Shiang-chyi (Chen Shiang-chyi). There’s a painful distance between them and they have sexual problems which may or may not be related to Hsaio-kang's career as an actor in porn. It's implied that the trouble is not isolated to this one couple but is societal, symbolized by Taiwan’s drought leading to the replacement, en masse, of water with watermelon juice; the perverse standing in for the natural. Similarly sex is replaced with porn, the cinematic realization of sexual fantasy.

Therefore, The Wayward Cloud becomes a romantic comedy corrupted, its early, gently comic sex scenes gradually accumulating a violent, sinister tinge and then giving way to a deeply disturbing conclusion in which the simple pleasures of the film and any audience identification with its main characters are utterly spoiled. The couple is finally able to achieve some sort of sexual intimacy, but only indirectly through pornography, both its fantasy and the ugly reality behind it, which is equated with voyeurism, corruption, alienation, and rape.

These associations are created incrementally, using images and fantasies from porn then ironizing them more and more with each appearance. The first sex scene is mostly a joke, and a silly one, using a watermelon as a stand-in for genitalia, and later scenes are increasingly desexualized through Tsai’s signature so-called "slow cinema” style: long-take long-shots with awkward mise-en-scene, leaving the porn film crew visible in the frame. He also uses the imaginary cinematic world of his filmography to add a distasteful dimension to one sex scene: Hsaio-kang, ostensibly the same character as in What Time Is It There?, though he behaves differently, performs a pornographic scene (the first one with a sense of violence) with Lu Yi-ching, who played his mother in the earlier film.

The spontaneous sexual encounter between Hsaio-kang and Shiang-chyi in the adult section of a video store comes close to genuine romantic connection, but Hsaio-kang stops it for reasons left unexplained. Impotence? Discomfort? Emotional distress? One could intuit from Tsai's precise single-shot framing that it may have something to do with the porn videotapes that line the shelves around the couple. Their physical connection is fulfilled in the next shot, as they dance together across a bridge, a rhyme with the film’s choreographed numbers implying the sweeter possibilities of reality imitating fantasy, along with Shiang-chyi's casual humming, dancing, and playacting throughout. But by the end of the film, those hopes are handily wrecked, suggesting that the indulgence of sexual fantasies through porn gets in the way of achieving them in any kind of healthy way, and violently perverts their real life fulfillment into, at its most extreme, unspeakable horror. After seeing The Wayward Cloud, can you ever look at rom-coms, musicals, or porn the same way again? Can you ever love or fuck the way you did before? Would you want to?

The Wayward Cloud is playing as part of Bijou After Hours on Saturday, September 21 at 10PM for the Grand Opening of the FilmScene Chauncey location. Free for students.

The above text is adapted from the paper "Sexual Fantasy and Social Realism in the Films of Jia Zhangke and Tsai Ming-liang," written and presented by the author in 2016.